How I Use the Internal Family Systems Model

IFS is one of the primary frameworks I draw on, alongside peer support and systems thinking. What follows is not a technical explanation, but a grounded account of how I understand and practice parts work, especially in relation to intensity, inner conflict, and extreme states.

I came to IFS because I needed a way to understand powerful inner experiences without treating myself as broken or trying to suppress what was happening inside. For a long time, I assumed that overwhelming thoughts or emotions meant something was fundamentally wrong with me. That belief didn’t help. Learning to relate differently did.

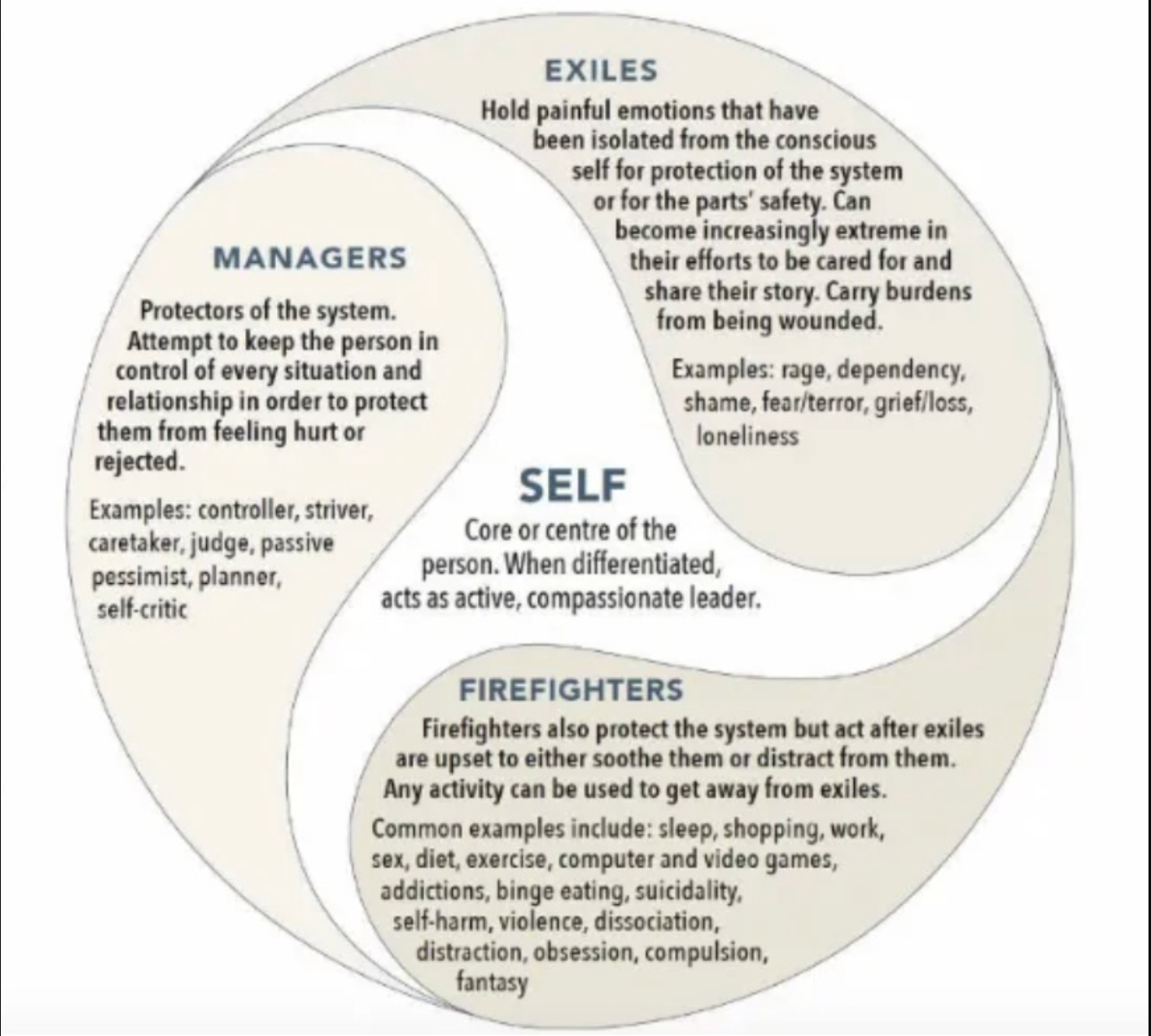

IFS offered a frame that felt both simple and radical: that we are made up of parts, and that even the parts that cause trouble are trying to protect something. This applies whether you’re dealing with anxiety, depression, trauma, relationship patterns, or more extreme states. Instead of asking “What’s wrong with me?” the work becomes “What part of me is showing up right now, and what does it need?”

What I appreciate about IFS is that it doesn’t ask you to get rid of anything. It gives you a way to slow down and listen without being overtaken. You don’t have to buy into a theory or use therapy language to do this work. Most people already recognize what it’s like to feel conflicted, hijacked, or pulled in different directions. IFS just gives us a way to work with that experience rather than against it.

At the center of this approach is what IFS calls the Self. I don’t think of Self as a perfected or spiritualized state. I think of it as the capacity to stay present, curious, and grounded when things are hard. Sometimes that’s subtle. Sometimes it comes and goes. My role is to help create enough safety and pacing for that capacity to show up more often.

My experience working with psychosis informs how I approach all inner work. Extreme states make it clear how important containment, relationship, and shared reality are. They also make it clear how easily inner experiences can escalate when someone is alone with them. Whether someone is navigating voices and altered realities or more familiar struggles like shame, panic, or burnout, the principles are similar: slow down, get curious, don’t isolate, don’t rush meaning or action.

I use IFS alongside systems thinking, peer support, and tools like T-MAPs because inner experience doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Our parts are shaped by families, culture, trauma, and power. I’m not interested in inner work that ignores context or turns suffering into a purely individual problem.

IFS, as I practice it, isn’t about making people more “normal” or easier to manage. It’s about helping people build a more workable relationship with their inner world—so intensity doesn’t have to run the show, and so more choice, connection, and care become possible. The rest of this page, and the examples that follow, show how that question guides the work in real situations.

IFS in Practice

Below are a few examples of how I use parts work in real situations. These are not case studies or how-to guides. They’re snapshots of how this approach shows up when people are working with intensity, shame, inner conflict, or altered states.

Working with shame loops without collapsing into self-blame

When “I’m a terrible person” becomes a closed circuit, and how parts work creates space for dignity and accountability.When intensity feels meaningful but destabilizing

Slowing things down without dismissing insight or imagination.Learning to speak for parts instead of being overtaken by them

How language alone can change pacing, choice, and self-trust.

Read the full examples here. (coming soon)